Middle East

Middle East/North Africa

Palestinians: Getting Poorer

|

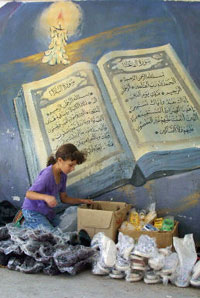

| West Bank, Sept. 3, 2002: A young Palestinian girl sells shoes in the streets of Askar refugee camp, near Nablus (Photo: AFP). |

Outside the zakat, or alms, center in Ramallah's Al Amari Refugee Camp, religious men collect donations of charity to distribute to the poor. Abu Jamil, a father of four, was waiting in line with many others. He had been waiting for about an hour when I found him in the large crowd of people requesting the equivalent of US$30 that is provided as charity to the people of Al Amari Refugee Camp. Embarrassed about his economic situation, he asks that his real name not be used.

"This is one of the forms of aid that I receive on about a monthly basis," explains Abu Jamil. Ever since he lost his job as a laborer in Israel, Abu Jamil and his family have been living off charity and food aid collected from various agencies. In total, however, he never manages to scrape up more than $150 a month.

Another half hour later, Abu Jamil receives his money and heads home, stopping along the way at a vegetable vendor to purchase tomatoes and potatoes. He has invited me to his home, and a first glance at his furniture indicates that the family was once reasonably well-off. Only in the kitchen, where I meet his wife, is their poor economic situation obvious.

First thinking I had arrived to offer my own material assistance, Um Jamil opens the refrigerator door to show me just how bad their situation is. The family's refrigerator is completely empty, despite that it is Ramadan and normally a time of bounty in Palestinian society. Families want to serve their best after a long day of fasting.

"Fabulous. Tonight we will eat fried potatoes and tomato stew," announces Um Jamil to her four children. She is thrilled with the vegetables Abu Jamil brought home, and their children looked excited at the prospect of this meal.

But what she planned to prepare is normally only a side dish. I understand the children's joy only when I realize that they break their Ramadan fast with bread and tea on those days when Abu Jamil doesn't have the funds to purchase other food.

Far from being an anomaly, the dire straights of this family are representative of the unprecedented poverty rising in the Palestinian territories, resulting from the hermetic siege imposed by Israel for more than two years.

Economic distress in the Palestinian territories has increased significantly since Israeli forces placed intermittent curfews on various cities in the West Bank in March. Most offices and workplaces were paralyzed. Poverty and unemployment have since reached their highest levels.

According to the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, 66 percent of Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza Strip are now living under the poverty line, a benchmark calculated at a monthly income of 1,650 NIS or US$250, for a family of two parents and four children. Surveys conducted by the Central Bureau of Statistics also indicate that the unemployment rate has risen to 45 percent and continues to increase under the sustained siege of the Palestinian territories.

"At the present time, when most cities in the West Bank and Gaza are under curfew and there are restrictions on movement between Palestinian cities and villages and Palestinian laborers are barred from working in Israel, three quarters of the work force of 750,000 people are unable to work," says Minister of Labor Ghassan Al Khatib. "Fifty percent of them are out of work for good, and 25 percent are unable to get to their workplaces."

Palestinian families are experiencing this phenomenon in a number of different ways. "Poverty has had numerous economic, social, and educational ramifications on Palestinian families," Al Khatib said. "A family whose head is unemployed and who is living under the poverty line is not getting enough food and money to take care of its health needs and education. Children in particular are getting sick as a result of poverty."

The United Nations Relief and Works Agency, UNRWA, issued an alert on Nov. 19 that 25 percent of Palestinian children are suffering from malnutrition due to the severe shortage in nutrients they receive. General Commissioner of UNRWA Peter Hansen blames human shortcomings for the dire straits of Palestinian children. The collapse of the peace process and Israeli clampdown on areas meant to be under the control of the Palestinian National Authority are the roots of this phenomenon, he says.

"There are new phenomena that have appeared as a result of the current economic situation, such as dropping out of school and child labor," agrees Al Khatib. "There is the danger of a generation of parents that doesn't have the awareness or basic life skills that are necessary to raise their children in a healthy manner. These things endanger the health and the social and psychological well-being of children."

Walking in Palestinian streets, one inevitably encounters children selling chewing gum, stickers bearing Quranic verses, and tissues for the price of a few shekels to aid their families. This was how I met Abu Jamil. His 12-year-old son tried to sell me chewing gum in the street. When I asked him why he was working, he replied, "My father hasn't worked for two years. He tried to find work in Ramallah but he had no luck and we don't have enough money to buy food with. And so I decided to sell chewing gum to earn some money to help my family."

Jamil is still in school and wants to complete his education so that he can become an engineer. He studies at the UNRWA school in the Al Amari Refugee Camp, hustling in the streets after he finishes his classes.

The Palestinian Authority has managed to do some things to stop the eroding effects of poverty. "A number of projects have been devised to help the labor sector," says Khatib. One of these is the employment and social protection fund, a joint project established by the Ministry of Labor and the International Labor Organization. It seeks to provide employment for particularly vulnerable groups, such as families headed by women or handicapped individuals who are out of work.

"If we want to assist everyone under the poverty line in these difficult economic circumstances, then we need US$13 million right off," says Director of the Palestinian Economic Council for Development and Reconstruction Mohammed Shtayyeh. "This would revitalize the Palestinian economy in all economic sectors, from helping families to supporting the private sector to repairing the damage to the infrastructure caused by the Israeli forces."

Shtayyeh says that, otherwise, the Palestinian economy is near paralysis and collapse. Income sources that have kept the economy afloat are slowly flagging. "The most important of these is the Palestinian National Authority's income from taxes and other sources. There were also the transfers made from laborers in Israel, which once were as much as US$800-$900 million per year. This was in addition to the fees and customs taxes and other funds that Israel has stopped transferring to the Palestinian National Authority."

Most economic activity, particularly that of the private sector, has slowed to 30 percent of its prior capacity, putting the Palestinian economy in severe decline. The Palestinian Authority has become entirely dependent on donations from Arab and other countries to cover its financial needs. The Authority requires US$60 million per month to pay the salaries of its 132,000 employees, in addition to another US$20-$30 million for operational costs. Now, however, the Authority is receiving only US$10 million a month in taxes, putting it at a deficit of US$75-$80 million.

This downward slide will only stop with positive political developments, says Shtayyeh. "If the siege and closures continue, along with the security wall and the roadblocks at the entrances to Palestinian towns and villages that break the geographic continuity of Palestinian areas, then the economic situation will continue to decline," he said. "We need a total of four to five years to return the Palestinian economy to the state it was in during 2000, when the deficit was limited and employment was high and less than 12 percent of the population was living under the poverty line," he predicts.